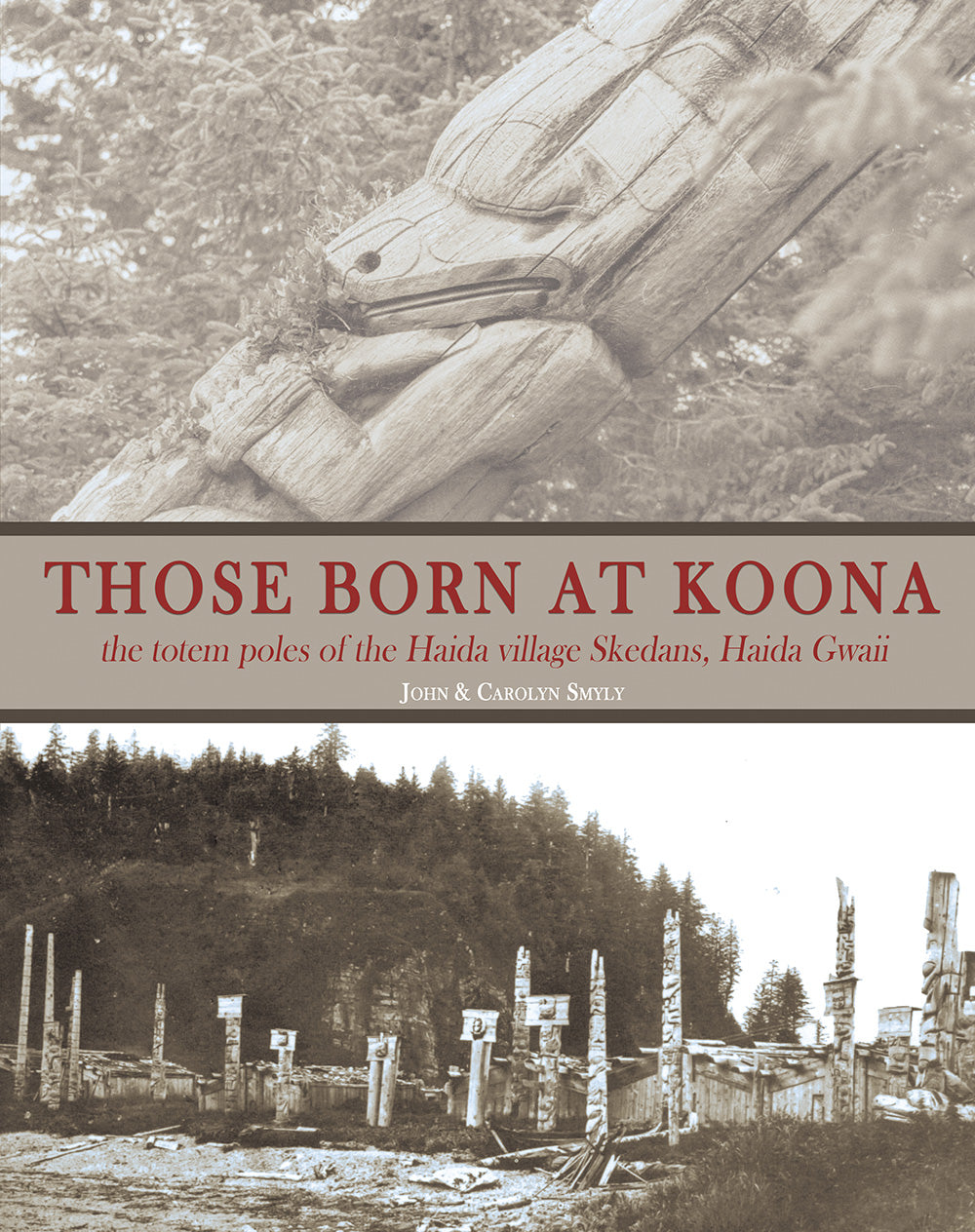

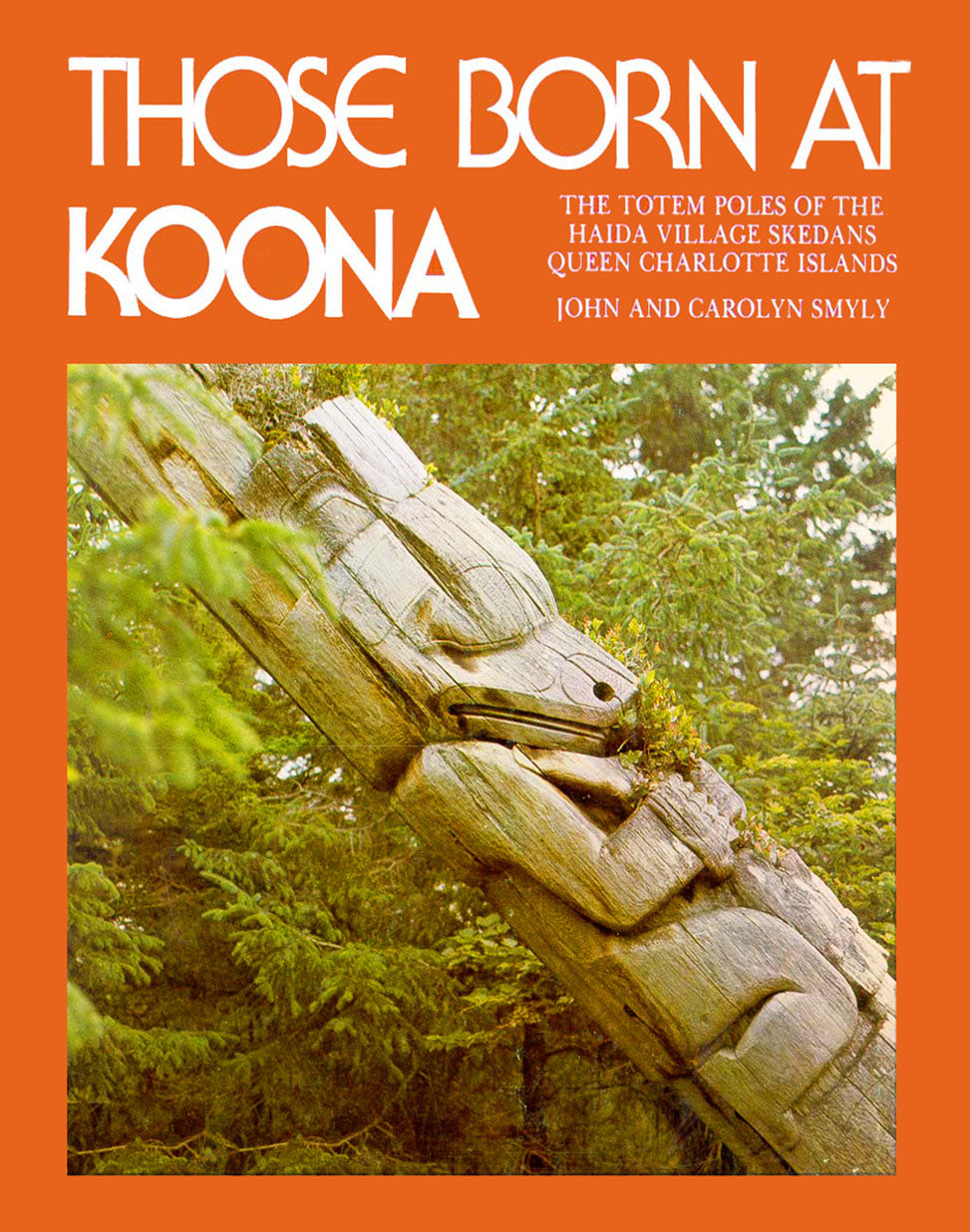

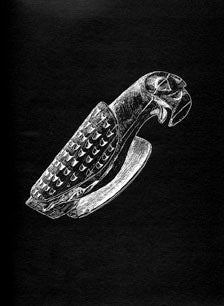

Those Born at Koona: the totem poles of the Haida village Skedans, Haida Gwaii

Details

By: Smyly, Carolyn & John

ISBN: 978-088839-101-8

Binding: Trade Paper

Size: 8.5" X 11"

Pages: 124

Photos: 75

Illustrations: 75

Publication Date: 2018 Reprint (Orig. 1973)

Description

PR Highlights: The story of the totem poles.

PHOTO Highlights: B/w photos throughout the book.

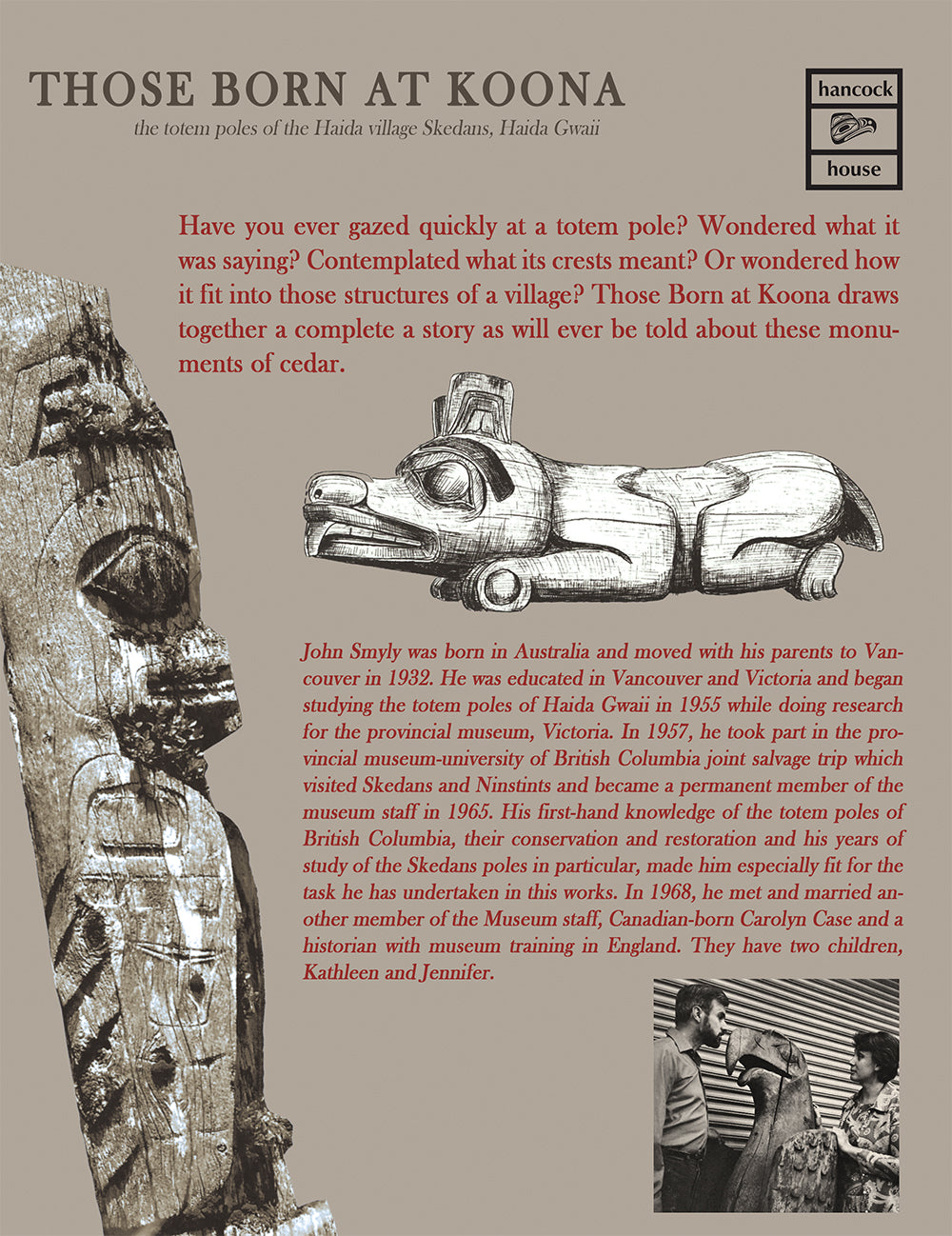

Have you ever gazed quickly at a totem pole? Wondered what it was saying? Contemplated what its crests meant? Or wondered how it fit into those structures of a village? Those Born at Koona draws together a complete a story as will ever be told about these monuments of cedar.

Author Biography

John Smyly was born in Australia and moved with his parents to Vancouver in 1932. He was educated in Vancouver and Victoria and began studying the totem poles of Haida Gwaii in 1955 while doing research for the provincial museum, Victoria. In 1957, he took part in the provincial museum-university of British Columbia joint salvage trip which visited Skedans and Ninstints and became a permanent member of the museum staff in 1965. His first-hand knowledge of the totem poles of British Columbia, their conservation and restoration and his years of study of the Skedans poles in particular, made him especially fit for the task he has undertaken in this works. In 1968, he met and married another member of the Museum staff, Canadian-born Carolyn Case and a historian with museum training in England. They have two children, Kathleen and Jennifer.

Book Reviews

It is becoming increasingly evident that three schools of thought are emerging from what, up to this date, has been a formless group working with the undigested Indian material of the Canadian west coast. If we look at this "formless group" from an historical perspective, we find Boas, Barbeau, Swanton and others doing their work; they are followed by writers such as Katherine Judson and Hugh Weatherby. Then there are the Indian artisans, such as Clutesi and Reid.

Of the three groups, the second can be excepted from serious consideration. Although there is a certain validity to keeping our interest alive through retelling stories, this style does not further our knowledge. It is time that our knowledge matured beyond those minds that equate simplicity with childishness. One cannot respect the Indian artisans enough: this third group is fighting an uphill battle against society, education and history. But in 1974 it is difficult to respect the art to the same extent one respects the artist. Today their art is fashionable just as Eskimo sculpture is; and just as sixty years ago African art was the rage in Berlin and Paris. Tomorrow the Indian artist will face the problem that his grandfather faced when the missionaries "liberated" him from tradition. There is little to be learned from the carver working in traditional patterns.

The only group that is developing within itself and increasing our knowledge is the one headed by Boas and Swanton, followed by Barbeau and Wingert, then Holm. Now we can add Those Born at Koona to the list of necessary books for any serious study of British Columbian Indians. Today Koona (Q'ona) is better known as Skedans, a village which once thrived on the eastern shore of Louise Island, in the Queen Charlotte group. Almost nothing is left at that spot which Emily Carr found to be so without "sham" in 1907. Even then it was a ghost village rapidly returning to the soil and forest. Today a logging camp is based where the town once stood, a few poles lean into the wind and nothing more.

It is probably safe to say that no one knows Koona better than John Smyly. In 1956 Smyly was commissioned by the Provincial Museum at Victoria to produce in replica three Haida houses and a representative group of poles — which he did at a scale of five-sixteenths of an inch to the foot. In 1957 he took part in a salvage trip to Koona and Ninstints. In 1965 Smyly became a permanent member of the museum staff and one of his first jobs was to build a model Haida village. He tells us that he chose Koona because of "the variety of its poles and the beauty of its natural setting."

In Those Born at Koona Smyly has built Koona again — with words and pictures. Beginning at one end of the village he has worked through the 27 houses and 56 poles known to be at Koona in the closing years of the last century. Fortunately, Dr. George Dawson took photographs of Koona in 1878 when the houses were in use and the poles erect. In 1897, Dr. C. F. Newcombe photographed the site and in 1907 Emily Carr took a few photos. "Skedans," a chapter from Carr's Klee Wyck should be read in conjunction with Those Born at Koona. If it were not for these pictures, and the notes kept by Newcombe and others, Smyly would have faced an impossible task. Koona was built of wood; and very little survives the damp of the British Columbia rain forest, not even resilient cedar, the primary wood of the people of Koona. One of the more intriguing facts to emerge from this book is the house names. It has long been known that the totems are ideographic; the poles cannot be read, as was long believed, but each figure, no matter how small, meant something to the carver and to the owner of the pole. Because the Haida had no written language, the owner's exact knowledge of the pole died with him. In contrast, the mythology of the Haida, like the mythology of the other coastal tribes, was not ideographic, nor was it very cohesive. In fact it was as opposite to the formal visual art as can be imagined. In the light of this distinction between oral and visual art, it is interesting to find houses with names such as "Peaceful House," "Eagle-Leg House," "House Raven Found," "People Think of This House Even When They Sleep Because the Master Feeds Everyone Who Calls," and, best of all, "Clouds Sound Against It (As They Pass Over)." These names were given to John Swanton by Chief Skedans when he was already an old man with a fading memory. But we do know that each house had more than one name: "House People Always Think Of" was also known as "Raven House." Skedans itself was also known as Grizzly Bear Town due to the numerous bear appearing on the totems. These names are poetic and ideographic, just as the interplay of form and space in the totem is poetry. The awareness of this poetry, and the knowledge that more than we know or suspect may lie beneath the surface of the carvings, stories and paintings, give us a better appreciation of places like Koona.

Volumes such as Those Born at Koona will be important because they are our doorway into the aesthetics of the Haida. Today they are bought, as the art is, because "primitive" is fashionable and it all makes good conversation. But this curiosity will die, all fads do. And when that happens we will be left with a few solid pieces of art and less than a dozen books on what Haida meant.

From these books, from these pieces of art, we will be able to recreate the intellectual, social and artistic milieu which flourished when the totem and the myths began to grow from idle carvings and fire-side tales, into the art we have today. As Herschel B. Chipp and Carol F. Jopling are proving in their work with primitive art and culture, the psychological depth lying beneath the surface of myth and art is staggering. Except for Barbeau, no one has really approached the north Pacific Indian cultures with anything near the imagination and insight of a Levi-Strauss or Robert Graves. Until this happens our appreciation and knowledge of the art and myth will not mature.

But all of this is still in the future. Those Born at Koona is important for what it is today and not for what it may hypothetically lead to tomorrow. This is a strong book, and an extremely accurate one, but it too is brief. Between 1836 and 1841, John Work counted 738 people at Skedans and thirty-seven years later, in 1878, Newcombe found the village almost entirely deserted. Why? Smyly is correct to a certain degree in attributing it to smallpox, but the missionaries and canneries and salteries with their money had much to do with it as well. This is something which deserves more than the one sentence answer we find in Those Born at Koona.

While it is recognized that no photos of Koona in its heyday exist, it would have been helpful if photographs of Skidegate, or another large village, had been included in this book. This would give the reader a sense of the village's true size. The feeling one receives from Those Born at Koona, is one of space, tidiness and planned architecture. Nothing could be further from the truth. And, worse yet, the impression stays with us long after we close the book. It shouldn't. A village was a busy community, it was life. This is what we should remember. The Smylys tell us that Koona was fortunate in that it was a peaceful village. From Swanton we learn that Koona had a firm relationship with the Tsimshian at Kitkatla, and that they imported stories and customs from them. It would be interesting to know why this village was so peaceful. It was rare for the different clans or phratries to get along well, not to mention their relationships with other tribes. But we are not told and we read on wondering.

The nature of the "whys" that continually come to mind suggest that the Smylys are hesitant to stick their necks out and become authorities. There is no apparent reason why they shouldn't become the experts on Koona. It is obvious that they know Koona as no one else does; and, even though much of the information is sketchy, they move with ease through Koona and the information surrounding the village. This refusal to come to terms with their knowledge, along with a certain self-deprecating note —which flows like a current through the book — is sounded quite early: We hope that the errors and omissions we may have made will cause some Haida person to say, "I can do better than that/' and set about the task as it should be done, written and illustrated by the descendants of those who once lived at Koona. This attitude echoes a statement made to me a few years ago at Kitsi-gas, "You're a white man, how can you understand what we're doing?" This type of thinking would rewrite history, and what it would do to our cultural heritage simply defies the imagination. But it is not an accurate attitude. Art is art, and it's open to anyone with the intelligence and knowledge to study it. The same can be said about myth -— is it possible that we should forget Frazer's work since he's not a Greek, or Levi-Strauss' because he's not a South American Indian?

Those Born at Koona would be an enduring classic had the authors taken a few drastic steps toward being the final word. As it is, the book is the best of its type — and it belongs beside the books of Boas, Barbeau, Swanton and Wingert.

--Charles Lillard, UBC 1973